À la carte (May 6, 2025)

The enduring appeal of literary projects authored by the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, a fresh take on the weaponization of anti-semitism, and recent telepathy skepticism.

There are no palette cleansers this week! Move right along if you are looking to get lost in something light. But if you are willing to be gripped by something not so light, read on.

Another Holocaust book

One of my favorite literary subgenres is researched memoir or auto fiction authored by a descendent, typically a grandchild, seeking to weave together the disparate threads of her ancestors’ lives in order to answer some fundamental unanswered question. Specifically, I’m a huge fan of memoirs that braid the biographical history of an ancestor or two with the author’s own present-day quest to fill in some gap in the family lore. I love archival and genealogical research so much that someone else’s research process reads to me like a hero’s journey. I am fascinated by the author’s quest for an answer to an unanswerable question—who were our ancestors, really? And what really happened to them? And why do we feel like we need to know in order to know who we are?

More often than not, when I’m picking up a book that falls within this subgenre, it’s authored by the grandchild of a Holocaust survivor (like East West Street by Philippe Sands, or When Time Stopped by Ariana Neumann), or the grandchild of someone who had some role to play in Holocaust—i.e., a French resistance fighter, or a Nazi collaborationist (as in The Propagandist by Cécile Desprairies). I’m likely drawn to these stories because the stakes of the author’s quest to fill in the gaps feel particularly high in the context of the Holocaust. Perhaps I’m drawn to these stories because I am still trying to accept the unknowability of my own Jewish grandfather. Perhaps it’s just that there have been many such stories published in the first quarter of the 21st century, likely because it is my generation asking the questions that our parents’ generation were too hesitant to ask their own parents. Sometimes the stories are published as straight memoir, other times as autobiographical fiction. Always, we know how the story ends. But we are reading not for an ending, but to fill in the gaps.

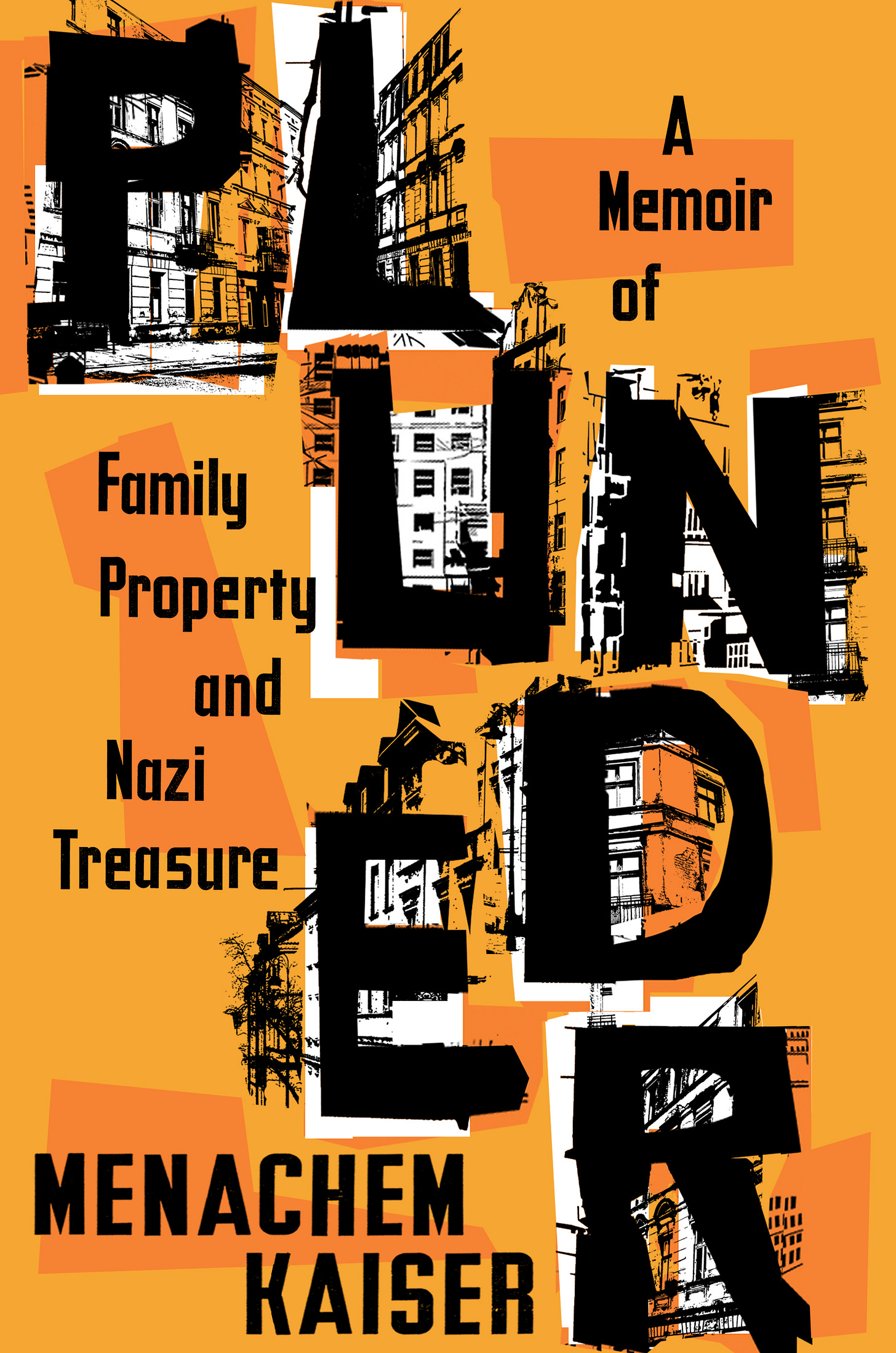

Menachem Kaiser’s Plunder—A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure has been on my list in my Notes app (of books I’d like to read) since 2021, when it was first published to great critical acclaim. And yet Plunder only made its way into my hands last week when I was looking for a new book to begin, and decided to search Libby for something that wasn’t a new release and was less likely to have a long hold list.

I was immediately engrossed by Plunder, in which Kaiser, grandson of a Holocaust survivor, documents his efforts to reclaim the apartment building owned by his family in Poland before the war. But navigating the absurdity of the contemporary Polish bureaucracy is only one strand of the tightly woven thread running through this novel. In a parallel plot line, Kaiser encounters a world of Silesian hobbyist treasure-seekers who believe gold lurks under rural Poland in a vast, but virtually unheard of, Nazi tunnel complex. Unbelievably, there is a connection between these two threads—one that I didn’t expect when I picked up this book and that Kaiser didn’t expect when he set off for Poland.

Kaiser is my favorite kind of narrator—thoughtful but frank, poignant but sharply funny. He never stops analyzing his motivations, or asking open-ended questions. “I do not trust the genre I am writing in, that of the grandchild trekking back to the alte heim on his fraught memory-mission,” he writes. “It’s too certain, too sure-footed, meaning is too quickly and too definitively established; there is no acknowledgment of the abyss, the void, the unknowable space between your story and your grandparents’ story.” While I disagree with Kaiser’s claim that the other grandchild memoirists fail to acknowledge unknowability, Kaiser’s literary project undoubtedly centers it. Unknowability is a central theme, even as he learns more than he ever expected.

Yes, another Holocaust book

I had just finished Plunder a few days earlier when I picked up a paperback copy of The Postcard from a table at my local bookseller dedicated to Europa Editions. I had no recollection of ever coming across the novel’s cover or title, despite the fact that it was published in France in 2021 and in translation the U.S. in 2023, and the backcover’s blurbs suggested it had been a sensation. How had I missed Anne Berest’s multi-generational family saga?

While billed as fiction, The Postcard is plainly autobiographical. Berest is the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor, and the novel follows her efforts to uncover who sent her family a postcard in 2003 with the names of four of her relatives killed at Auschwitz. You might think you can’t read another book about Auschwitz. But you should read this one. It is gripping, vivid, and haunting.

I don’t think I’ve ever written about a book here that I haven’t finished. I started The Postcard on Friday night, and as of Monday evening, I’m 321 pages out of 467 through. I cannot wait to finish writing about it here so I can get back to reading it. It is the sort of book you read until you fall asleep and you wake up thinking about. I feel confident that I don’t have to finish The Postcard before I can recommend it. As with Plunder, I’m not reading it for its ending. I am expecting the unknowable to remain unknowable.

I think part of what makes the stories of our grandparents so compelling is that the 1930s and 40s were recent and modern enough for a limited paper trail to still exist—it is often a photo or an incomplete record that provides the grandchild with an initial spark of curiosity— but far enough out of reach to guarantee the narrator’s questions will ultimately remain unanswered. I keep reading these stories because what is life if not a quest for answers to unanswerable questions.

A very nuanced conversation on anti-semitism

Between Plunder and The Postcard and The Ongoing Situation At Home And Harvard And Abroad, I’ve been thinking about anti-semitism even more than usual. The social media bubble in which I exist makes it feel increasingly impossible to be concerned about both anti-semitism and the killing of Palestinians by Israel. And I am exhausted from doing the mental gymnastics of just trying to explain to myself how I can be both concerned about anti-semitism and the weaponization of anti-semitism to further the right’s ethnonationalist and autocratic agenda.

I came across this episode on the London Review of Books podcast last week and it was one of the smartest, most nuanced, most helpful conversations I have heard on the topic of weaponizing anti-semitism, and the decoupling of anti-racist and anti-semitic politics on the left. I still feel very very worried, but I feel a little less alone after listening.

A zeitgeisty article and the surrounding debate

A few months ago I wrote about The Telepathy Tapes, a chart-topping podcast that purports to document the abilities of nonverbal autistic children to communicate telepathically. As told by Ky Dickens, the podcast’s host, the abilities of these nonverbal people offer irrefutable evidence of telepathy and other psychic phenomena.

I started listening to The Telepathy Tapes as a skeptic. When I finished listening, I was, if not a believer, also not a total skeptic. What The Telepathy Tapes purported to document was, to me, astonishing and incredible, but also not totally inconsistent with my agnosticism. I remained curious but not curious enough to spend money to subscribe to the The Telepathy Tapes’ website in order to watch video footage of the tests recapped on the podcast.

But obviously the claims made by The Telepathy Tapes are a tough sell for minds more skeptical than mine. And unsurprisingly, there have been subsequent efforts to debunk The Telepathy Tapes and discredit its host. Last week, a friend of mine with a skeptical mind sent me Elizabeth Weil’s recent article in New York Magazine, told me it validated all her preconceptions, and wanted to know my thoughts.

My thoughts? Weil’s piece is a very compassionate hit job. She is careful in her treatment of the the families of nonverbal children, and generous towards mothers who are desperate to communicate with their children, even as she claims to debunk the conclusions of The Telepathy Tapes by discrediting the methods used by the nonverbal people on the show to communicate. These methods—various forms of “facilitated communication” or “spelling”—require a spelling partner (often the child’s mother) to hold a letter board from which the child selects letters in order to speak by spelling. To discredit both spelling and the notion that nonverbal people can communicate telepathically with their spelling partners, Weil follows up with some of the families featured on The Telepathy Tapes and tries to recreate some of Dickens’ experiments. By her telling, they don’t work. The spellers fail the test when their spelling partner doesn’t know the correct answer. Her explanation? Spelling is not spelling at all, but can be explained by the “ideomotor effect,” by which the nonverbal speller is guided by the spelling partner’s subconscious cues.

It has been months since I’ve listened to the podcast, but it strikes me that the ideomotor effect can’t explain everything that is purportedly documented on The Telepathy Tapes. And The Telepathy Tapes does grapple with spelling’s skeptics, most seriously in a final bonus episode featuring

, a scientist who also sought out to debunk the Tapes and ended up concluding that the ideomotor effect really can’t explain the phenomena documented by Dickens. Kramer ultimately neither validates nor debunks the telepathy claims made by the Tapes, but concludes that a serious skeptic of telepathy cannot rely on the ideomotor effect. (You can read her work here.)For now, I’m comfortable with not knowing exactly what I believe. I’m okay with a little mystery.

Caroline, this is exactly what I needed to read right now for so many reasons. Thank you for your reading and writing work and the way you navigate the in-betweens.