Let's talk about acne

On the secret shame of bad skin, the lure of vanity, Rio Viera-Newton, and the false promise of ProActiv

With my wedding now only four months away, the compulsion to look like some idealized version of myself by the time I walk down the aisle is setting in—hair long and glossy, body toned and thin, skin clear and glowing. I don’t know how a bride can possibly avoid the pressure to achieve perfection. Not only are girls more or less inculcated from birth to buy into the notion of a wedding day as a realization of fairy tale princess mythology, but spending all of the time and money that you can afford (or can’t afford) on your appearance on your wedding day is a completely normalized bridal behavior, reinforced by idle woman-to-woman chitchat as much as it is by Instagram and bridal blogs. Dropping something off at a tailor over the weekend, I heard a bride share to another bride that she was “90% of the way” to where she wanted to be on her wedding day. (I quickly forced the impulse to score myself out of my brain, knowing instantly that I would score myself less than an A-.) A Google search for “bridal body workout” yields over 14 million results. Perfection on one’s wedding day is not just a goal, but a norm.

For the moment, this compulsion still manifests more as a pattern of guilty thoughts than a pattern of altered behaviors. Next week I will cut out sugar and do more HIIT workouts, I keep telling myself. Maybe. But where I have begun to invest time and energy and money is my skin. Having not experienced anything close to perfect skin since I was eleven years old, I am, of course, completely obsessed with clear skin, obsessed with it in the way that a curly-haired ten year old lusts after straight hair. Not only do I begin and end the day with staring at and caring for my own skin, but I can’t restrain myself from noticing everyone else’s and comparing it to my own. Clear skin, in my eyes, is the ultimate marker of beauty. Since the age of 12, I have found every and any woman with unblemished skin beautiful. And as someone who can’t help but wish to feel beautiful on her wedding day, I find myself on what feels like the denouement of a decades-long quest for clear skin.

At 33, my imperfect adult acne-prone skin is still my great shame, and my great shame and self-consciousness about my imperfect skin is still my great secret, even though my skin itself is something that can’t be hidden (or couldn’t be hidden at least, until the pandemic and the ensuing rise of masking). Of all of the health issues I could suffer, I tell myself, acne is nothing. It is cosmetic. Only my vanity suffers. So I can’t eat as much cheese as I would like! My heart and lungs work just fine! But for years, in addition to the day-to-day anxiety of what was lurking under the surface on my chin or jawline, I feared that my skin would be this way forever. The idea of my wedding was oddly central to this anxiety. As my acne lingered into my twenties, I started to wonder whether I would ever be able to see what I looked like without it, whether it would ever get to a place where I could feel confident on my wedding day. How could I ever wear a wedding dress, when most days I wasn’t even comfortable wearing a tank top at the gym? Would the acne scarring on my back confine me to some sort of Orthodox turtleneck dress, for which I would have to make an excuse for an outdoor wedding in January?

I rarely speak about my skin. The last time I confessed my shame around my acne scarring, it was to a college friend who was advocating for a particular bridesmaid dress for a friend’s wedding. I expressed my discomfort with wearing the dress, which was almost as painful as exposing my back. It turned into a Thing and I was made to feel selfish and in the intervening years, I have wondered whether my self-consciousness about exposing my back was indeed petty and unfair, given that the rest of my friends felt beautiful in the dress. Vanity is a form of pride and is a sin, after all. And even if the vanity that I deplore in myself is a less a form of excessive admiration of my own appearance and more a form of excessive attention to it, it does feel like a moral failing, a vast waste of time and energy. But like obesity, an image-obessed society can make bad skin itself feel like a kind of moral failing—some sort of intangible lack of rigor or hygiene, something that makes one stand out as less than.

If I am ever interviewed by Vanity Fair, I know my answer to at least two of the 35 questions that Marcel Proust believed revealed an individual’s true nature:

What is the trait you most deplore in yourself? Vanity.

What do you most dislike about your apperance? My acne-prone skin.

Despite every other advantage conferred on me by the grace of the random luck of the universe, I have felt less than as a result of my skin for pretty much all of my time on Earth as a sentient being. I started to break out as early as fifth grade, and from there, it was a decades-long journey through different skincare regimens, at first prescribed by my mother and her esthetician (multi-step topical formulas that I would apply with little spoons, formulas that bleached my hairline blonde) and later a dermatologist (sulfur masks, creams that seemed to do nothing to my break-outs but which turned my skin dry and flaky and red). Then there was the Internet, the message boards of the early-oughts that my mother turned to, which swore by a two-step routine comprised of Cetaphil gentle cleanser and Neutrogena On-The-Spot benzoyl peroxide, which the message board said to smear all over my face every night. We went through a tube a week, turning my carefully-chosen periwinkle towels and sheets pink and yellow. I remember the dermatologist who swore by Olay Complete Daily Moisturizer. There was a Clinique Acne Solutions phase which, in eighth or ninth grade, at least seemed to bring a twinge of sophistication and elegance to my multi-step nighttime routine. Of course there was hope that the heavily-marketed ProActiv brand would be the solution, but again, it dried me out too heavily and did nothing to prevent break-outs. If I were to apply it today, the harsh smell and cold sting of Neutrogena Clear Pore Oil-Eliminating Astringent with Salicylic Acid would yank me back to the sting of rejection that followed not being invited to my crush’s bar mitzvah.

The adoption of each of these skincare regimens was surrounded with shame. Shame in going into my mother’s bathroom in tears in high school, confessing my despondency towards my skin. Shame in reluctantly accompanying my mom to the Nordstrom make-up counters, shame in letting her buy me Lancome’s newest acne-friendly foundation, shame in sitting in the waiting room of yet another dermatologist whose perfect blemish-free skin glared at me while she gave a cursory glance at my jawline and decolletage before prescribing an antibiotic. Shame in picking up the antibiotic at CVS—those casual outings at age 14 in which one always hopes and fears running into a crush— and having to explain why I was there, shame in having an allergic reaction to the antibiotic during my sophomore year performance in Brigadoon, shame in having my mother call the director to say that I wouldn’t be able to make the Saturday night performance while I sat in an oatmeal bath to cool my hives. Shame in being dragged to a facial at age 13 and hiding in the changing room and refusing to come out, my worst nightmare being having someone focus all of their energy and attention on my skin for 85 minutes. Shame in none of it working—even with absolutely every privilege—access to a dermatologist and facials and a mother who would drop hundreds at Nordstrom in an effort to put her daughter out of her misery.

Going on the pill helped a lot. Going off the pill was a nightmare. In college, I had bad acne on my back, acne that was bad enough that I dreaded taking off my shirt or being touched. The acne inspired a prudish persona that I was rarely brave enough to shed. Instead, I made my refusal to partake in casual hook-ups a personality, one my friends lovingly teased me for. I obsessed over blending in—blonde highlights, Barbour coat, Frye boots, Longchamp tote, Macbook—to hide what was different under my J.Crew merino wool sweater. Sometimes I wonder what I would have wanted if I had been brave enough to take off my clothes in front of someone other than the boys who confessed having had a crush on me for months.

By my mid-twenties, I started to wonder if my skin would ever get better. I went back on the pill. For a few blissful weeks during the summer, a tan would give me the confidence to reveal my back and shoulders in a spaghetti strap sundress during the right week of my menstrual cycle, but it was only a matter of time before a blemish or two would appear, confining me once again to tanks and tees. I started going to a dermatologist on Wall Street during my lunch hour, where I would sit under a blue light for 15 minutes and hundreds of dollars, with a goal of preventing break-outs and fading scarring on my back. I would pop by Zara on my way back to the office, combing the racks for a dress or a top that would make me feel sexy without revealing too much. I showed off my legs instead—mini dresses and cut-off shorts highlighting my toned legs that I worked endlessly in dance and kickboxing classes at Equinox. Rather than parade around the locker room in my underwear like the rest of the effortly gorgeous New Yorkers, in the Equinox locker room, I would quickly shimmy out of a towel and into my street clothes.

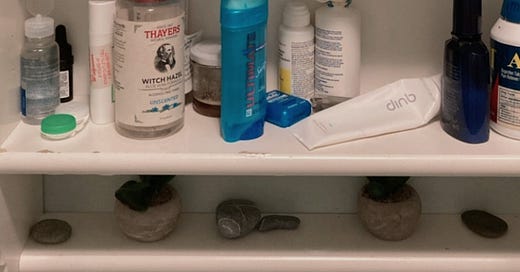

In law school, I went through an ayurvedic phase, cutting out dairy and relying on a stinky mix of scrubs and toners and oils that I largely mixed myself. A German ayurvedic practitioner expressed horror when I shared that I frequently ate raw kale salads for lunch. I have eaten hot lunches ever since. I stirred turmeric into aztec clay, made toners out of apple cider vinegar, and became militant about showering immediately after working out. Things started to slowly improve, my break-outs started to correlate with dairy indulgences. I became a disciple of Rio Viera-Newton and her skincare Google doc, which allowed me to feel for the first time like I was not alone. Seeing acne-care featured so prominently in New York Magazine inspired hope that I could be perceived as cool and fashionable even if I struggled with acne.

That was not the case in middle school, when I used to stare at myself in my bathroom mirror and wonder if I would ever be desirable underneath the blemishes and flaking. I would turn out the bathroom lights, allowing my reflection to be lit only by the residual light coming from my bedroom. I would press play on the bar mitzvah ballad, “This I Promise You” by N*Sync, and try to imagine what it would be like to slow dance with my crush-of-the-month and feel his hands creep down to my butt.

Now Instagram allows me to see myself with perfect skin whenever I want. I don’t even have to take a picture—I can just open the app, pick a filter, and turn the camera to my own face. Suddenly my forehead wrinkles are smoothed, my pores are airbrushed, and the lurking red cyst on my chin is gone. In moments of vanity, I am stunned to find myself attractive, but I am increasingly horrified by what I see when I glance at a selfie taken without a filter—circles under my eyes, blotchy skin, an oily t-zone—in stark contrast to the poreless airbrushed faces and bodies I am greeted by on my “Explore” page. I wonder what Instagram would have done to my already dejected psyche at age 13, whether it would have helped to see a version of myself that was beautiful, or whether being constantly inundated with unreal portrayals of perfection would have exacerbated my compulsion toward comparison.

I wish I could say that I have grown out of this obsession and made some peace with my appearance and my skin, that at age 33 I spend a little less time looking in the mirror and a lot less money on Strategist-approved Korean beauty products than I did at 25. After all, at some point after my wedding, I will go off the pill and who knows what will happen. But for now, the money I am spending on monthly appointments with a talented esthetician in the lead-up to my wedding speaks for itself and forces me to confess that I am still trapped in the self-imposed panopticon of excessive attention towards my own appearance, and with each week that passes, there seem to be more and more mirrors reflecting my appearance back at me.

And yet, reaching out to someone for help with my skin, as I have in the last couple of months, is novel. For the first time1, I am voluntarily confessing my woes, seeking advice, and turning myself over to someone else’s care. I am ready to admit that I have had enough with trying to manage my skin by myself with only the help of the Internet, and have had enough with trying to keep my frustration a secret.2 Perhaps I am just forcing myself to be able to point to some sign of growth, but I do think that allowing my skin to be looked at as a subject of discussion and study is a step forward. And perhaps so is talking about it, even if I recognize I am likely just trying to expiate my guilt of vanity. I am at least dipping a toe out of my shame. The esthetician, a favorite of local brides, is non-judgmental, knowledgeable, and reassuring. She has a plan, and the plan seems to be working. And on a monthly basis, she vacuums out my pores (at least that is what it feels like—the actual technique is known as hydrodermabrasion), applies peels, and performs a number of other delightfully relaxing techniques that leave my skin nourished and glowing by the end. She tells me not to wear make-up for a couple of days, and I feel brave and confident enough not to. Excuse my vanity — that’s a first.

For the first time since I was a teenager—Mom, you are not forgotten.

To my dermatologist mother-in-law who is certainly reading this, I know all of this will be hard to hear!

My heart breaks for you and all the pain, psychic and otherwise, that this has caused for you. We all have insecurities that influence our behavior and shape who we become but most remain needlessly secreted under layers of shame. How incredibly brave of you to bring yours into the light.

Relatable on countless levels, thank you for opening up on your own acne story!